The Once and Future Teacher

Tomer Doron / Op Ed

Posted on: April 2, 2013 / Last Modified: April 2, 2013

Software is eating up education. Ubiquity of connected devices, school budget pressures and dependency on the publishing industry make education a ripe target for software based disruption. As a result, an increasing number of software companies have been founded in recent years around the idea of making digital education smarter, cheaper and more accessible. The educational market has reacted positively to these new services: enrollment to online courses grew at 17% compared to only 1.5% growth in overall higher education, digital textbooks are expected to account for 35% of the textbook market by 2016 while blended learning is projected to reach a 98% penetration by 2020. As expected, such growth has created interest in the capital market: the edtech space has known several large transactions over the last three years and seen the birth of about half a dozen startup incubators.

Software is eating up education. Ubiquity of connected devices, school budget pressures and dependency on the publishing industry make education a ripe target for software based disruption. As a result, an increasing number of software companies have been founded in recent years around the idea of making digital education smarter, cheaper and more accessible. The educational market has reacted positively to these new services: enrollment to online courses grew at 17% compared to only 1.5% growth in overall higher education, digital textbooks are expected to account for 35% of the textbook market by 2016 while blended learning is projected to reach a 98% penetration by 2020. As expected, such growth has created interest in the capital market: the edtech space has known several large transactions over the last three years and seen the birth of about half a dozen startup incubators.

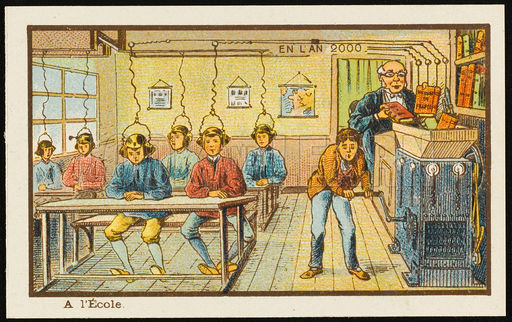

Many among these companies pursue the holy grail of an autonomous instructional system. The premise is that pattern analysis algorithms running on large amounts of student performance data will create a new system of learning centered around a narrow artificial intelligence. Such system would independently guide students, coming up with personalized recipes to mastering cognitive skills. In concept, this is not different from how mapping software helps you find the quickest route to the gas station. In practice, the scope and complexity required to achieve human like instruction is more similar to a self driving car than a GPS navigation system.

In recent years, narrow artificial intelligence has been gaining ground at exponential pace and is soon to become mainstream. Our favorite search engines, ecommerce sites and social networks are all based on massive adaptive algorithms. The aforementioned robocars are already driving themselves through the streets of Nevada and California, while the military has been using autonomous aircrafts (drones) for over two decades. Personal helpers such as Apple’s Siri are on every smartphone and consumer friendly robots are the next big thing. In 2011 IBM’s cognitive system known as Watson defeated two human champions in the game of Jeopardy! Now IBM announced it intends to make a smartphone version of this powerful intelligence. Ray Kurzweil, a world renowned inventor and an artificial intelligence pioneer, has recently joined Google. A move that hints exciting artificial intelligence applications are soon to be introduced by the search engine giant.

In edtech, companies like Knewton, Grockit, Dreambox Learning, and Carnegie Learning are years into the making of adaptive software. In January 2012, the Hewlett Foundation conducted a competition for automated essay scoring which yielded human equivalent results, a long sought-after feat. 2012 is also known to be the year of the MOOC with Stanford (Udacity, Coursera), MIT and Harvard (edX) offering massively open online courses which rely heavily on automation and machine learning.

While the current crop of adaptive educational software can be seen as primitive, the likely manifestation of artificial intelligence in the field of education is an autonomous instructional system. There is, however, a significant prerequisite: such system requires large quantities of data from which patterns can be extracted and algorithms trained on. While in many fields of science data can be easily collected, the education industry has not historically collected significant data. Neither in quality nor in quantity. Further, it is still very much an open question what data needs to be collected.

While the current crop of adaptive educational software can be seen as primitive, the likely manifestation of artificial intelligence in the field of education is an autonomous instructional system. There is, however, a significant prerequisite: such system requires large quantities of data from which patterns can be extracted and algorithms trained on. While in many fields of science data can be easily collected, the education industry has not historically collected significant data. Neither in quality nor in quantity. Further, it is still very much an open question what data needs to be collected.

Most educational software collects student results that are then correlated to learning context, learning style and resources. Such correlations are effective in yielding shallow personalization such as content recommendations and basic alerts. In essence, this is no different from product recommendations in ecommerce systems: useful, but by no means intelligent. To build a narrow artificial intelligence, we need to collect not only information about the learning results but information about the learning process. We need to monitor students continuously instead of sparsely. It is likely that we will need to borrow techniques from outside the field of education: monitoring human machine interaction and a/b testing (advertising, gaming); physiological sensors and brainwave scanners (quantifiedself, ehealth); augmented and virtual reality (gaming) and social graphs to name a few.

And so, the race is on. Many edtech startups attempt to build the platform of education, one that could collect data behind the scenes the same way Google, Amazon and Facebook collect data about their users. Others offer standardized cloud based educational data stores and application programing interfaces that can be used by educational app developers. Either way, the serious players are all trying to reach the critical mass of data required for the breakthrough. With heavy hitters like Sebastian Thrun, Anant Agarwal and Bill Gates joining the race, it is likely the winner will emerge over the next few years.

Privacy is always a major concern when it comes to data centric technology, and the data collected by such systems is very sensitive. Assuming we start collecting data at early childhood, we will end up with more than a decade of personal research backed by fine grained data. It will provide insight into students personalities, intelligence, strengths and weaknesses and could be used by commercial and government bodies alike to manipulate them to their needs. Can we stop this data from reaching potential employers, government agencies and other curious parties? Some suggest the rules of supply and demand will force future students to share their data as means of getting admitted to their school of choice or dream job, much in the way students share their GPA score today.

Traditional educational software is built around content and assumes humans will perform the instruction. In most cases, it is simple for schools to judge the content’s quality and how well it is matched to their requirements. Autonomous educational software is build around the instructional component and aims to replace the human with a machine. This begs the question: can we trust commercial companies to define these algorithms for us, or should educational software be regulated by the government? Traditionally, governments define the curriculum and train and monitor teachers. Performance data is kept within a government controlled ecosystem. Is society ready to let go of these principles and trust the machines and their builders? Many believe our government and existing education administration and will never allow for such revolution take place. Others say it is deep in our human nature to adopt tools that give us an advantage and this technology will be no exception.

Generally, teachers perform three functions: knowledge transfer and skill development; imparting community values; and social and behavioral training. In a world of an autonomous instructional system, teachers will give up the function of knowledge transfer and skill development to machines. Those educators that excel at this function will work for technology companies instead of schools. Their job will be to develop new teaching techniques [methodologies] which they will get to test and implement at a much larger scale than they do today. An example of how this could look like is the work of Eric Mazur of Harvard University on peer instruction and the aforementioned MOOCs.

Other teachers will focus on the remaining functions which are unlikely to be replaced by narrow artificial intelligence due to their social nature. They will also continue and perform a supporting role in knowledge transfer and skill development. An intangible is that a good teacher not only has the knowledge and skills to help a student succeed, but also care. This sense of care may be difficult for a machine to produce. That said, these social functions will also depend more on technology and data. One example is insights derived from the social graph and particularly the communication patterns between its members. Another is video analysis of social situations.

In both cases, we will see more specializations. The role of educators will shift towards a greater separation between theorists and practitioners. The former driving methodologies the latter applying them in classrooms. Great educators will focus on the science of teaching. They will become ubereducators and their methodologies will have global impact. Practitioners will be focused on the art of teaching, supporting students and guiding their emotional and social growth.

Many point out that our education system is rooted in the industrial era and that it is no longer able to perform its social role. Sir Ken Robinson explains it best. I believe the learning revolution is near. With access to a diverse world of knowledge, intelligent machines performing personalized instruction and humans focused on noncognitive skills, the future of education looks bright. That said, as a society we need to be prepared for such change and put checks and balances so that our core values, traditions and social nature are not lost in the process.

About the Author:

Tomer Doron is a technologist, entrepreneur and a Singularity University Alumni. His first company, PangeaTools developed mathematical models for virtual labs used in teaching physics, chemistry and biology. His current venture, Exploros, focuses on the virtual classroom and the use of real-time collaboration for developing non-cognitive skills.

Tomer Doron is a technologist, entrepreneur and a Singularity University Alumni. His first company, PangeaTools developed mathematical models for virtual labs used in teaching physics, chemistry and biology. His current venture, Exploros, focuses on the virtual classroom and the use of real-time collaboration for developing non-cognitive skills.

Related articles